Zen of Assembly Language

Assume nothing. I cannot emphasize this strongly enough—when you care about performance, do your best to improve the code and then measure the improvement. If you don’t measure performance, you’re just guessing, and if you’re guessing, you’re not very likely to write top-notch code.

Ignorance about true performance can be costly. When I wrote video games for a living, I spent days at a time trying to wring more performance from my graphics drivers. I rewrote whole sections of code just to save a few cycles, juggled registers, and relied heavily on blurry-fast register-to-register shifts and adds. As I was writing my last game, I discovered that the program ran perceptibly faster if I used look-up tables instead of shifts and adds for my calculations. It shouldn’t have run faster, according to my cycle counting, but it did. In truth, instruction fetching was rearing its head again, as it often does when programming the 8088, and the fetching of the shifts and adds was taking as much as four times the nominal execution time of those instructions.

Ignorance can also be responsible for considerable wasted effort. I recall a debate in the letters column of one computer magazine about exactly how quickly text can be drawn on a Color/Graphics Adapter screen without causing snow. The letter writers counted every cycle in their timing loops, just as the author in the story that started this chapter had. Like that author, the letter writers had failed to take the prefetch queue into account. In fact, they had neglected the effects of video wait states as well, so the code they discussed was actually much slower than their estimates. The proper test would, of course, have been to run the code to see if snow resulted, since the only true measure of code performance is observing it in action.

When you use a system service, you’re accepting someone else’s solution to a problem; while it may be a good solution, you don’t know that unless you check. After all, you may well be a better programmer than the author of the system software, and you’re bound to be better attuned to your particular needs than he was. In short, you should know the system services well and use them fully, but you should also learn when it pays to replace them with your own code.

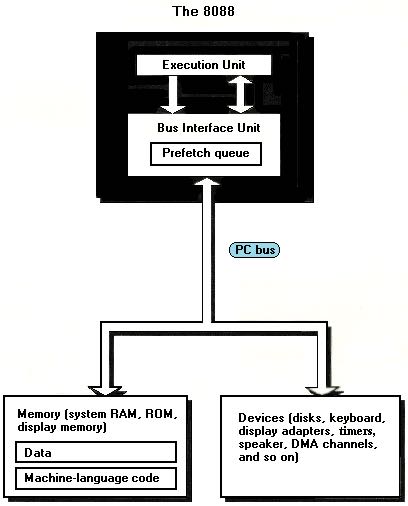

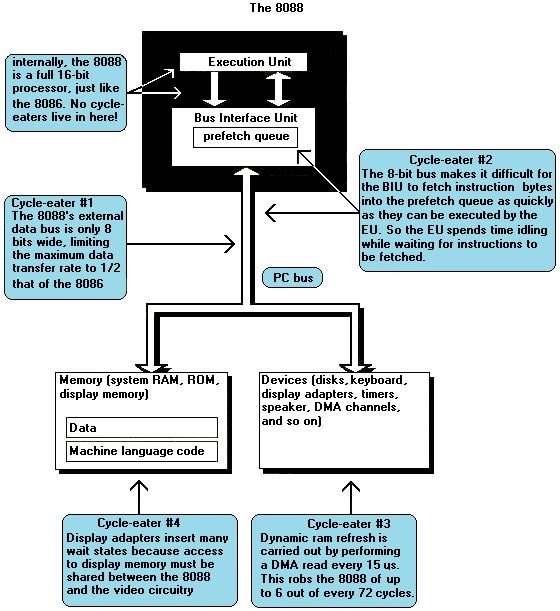

This view of the PC’s resources reflects the true nature of code as data stored in system memory. Code is stored in memory, so it must be fetched by the bus interface unit (BIU) just as data must; consequently, any cycle eaters present between system memory and the BIU affect the 8088’s code fetching speed as well as its data fetching speed. In addition, all memory access must pass through the BIU a byte at a time at a rate no faster than 1.2 bytes/microsecond (1 byte per 4 cycles), and serious bottlenecks can develop since code and data fetching can demand data transfer rates as high as 1 byte/209 nsec (1 byte per cycle).

The BIU contains all the memory-related logic of the 8088, including the segment registers and the Instruction Pointer, which points to the next instruction to be executed. Since code is just another sort of data, it makes sense that the Instruction Pointer resides in the BIU; after all, code bytes are read from memory just as data bytes are. In fact, the BIU takes on a bit of autonomy when it comes to fetching instructions. Whenever the EU isn’t making any memory or I/O requests, the BIU uses the otherwise idle time to fetch the bytes at the addresses immediately following the current instruction, on the reasonable theory that those addresses are likely to contain the next instructions that the EU will want. The BIU of the 8088 can store up to 4 potential instruction bytes in an internal prefetch queue, and other 8086-family processors can store more bytes still.

It’s worth noting at this point that the execution time specified by Intel for any given instruction running on the 8088 (as shown in Appendix A) assumes that the BIU has already prefetched that instruction and has it ready and waiting for the EU. If the next instruction is not waiting for the EU when the EU completes the current instruction, at least some of the time required to fetch the next instruction must be added to its specified execution time in order to arrive at the actual execution time.

Keep the following concepts in mind as you read on:

- All code is machine language in the end: don’t assume that anyone else’s code, even system software, is best suited for your needs.

- 1.2 bytes/us: at its best, the 8088’s BIU can transfer data no faster than this.

- The 8088 is not the lowest level: know how the PC’s hardware and bus affect memory access speed.

- Code is data: when the BIU and the PC’s hardware and bus affect memory access speed, they affect code fetching as well as data access, since code is just another sort of data in system memory.

Short and simple as the above list may seem, in it you will find every one of the concepts that form the foundation of the Zen of assembler—and with them the key to high-performance code.

The major cycle-eaters are:

- The 8088’s 8-bit external data bus.

- The prefetch queue.

- Dynamic RAM refresh.

- Wait states, notably display memory wait states and, in the AT and 80386 computers, system memory wait states.

The locations of the major cycle eaters in the IBM PC. Note that all the cycle eaters are external to the execution unit of the 8088.

Wait states出现延迟的原因在于,需要等待总线将数据从动态存储器中拿上来。

Wait states exist because the 8088 must to be able to coexist with any adapter, no matter how slow (within reason). The 8088 expects to be able to complete each bus access—a memory or I/O read or write—in 4 cycles, but adapters can’t always respond that quickly, for a number of reasons. For example, display adapters must split access to display memory between the 8088 and the circuitry that generates the video signal based on the contents of display memory, so they often can’t immediately fulfill a request by the 8088 for a display memory read or write. To resolve this conflict, display adapters can tell the 8088 to wait during bus accesses by inserting one or more wait states, as shown in Figure 4.6. The 8088 simply sits and idles as long as wait states are inserted, then completes the access as soon as the display adapter indicates its readiness by no longer inserting wait states. The same would be true of any adapter that couldn’t keep up with the 8088.

关于动态存储器刷新造成的延迟情况。和wait states延迟一样,它们都没有办法避免,但是编写高性能程序的时候需要考虑进去。

A bit of background: a static RAM (SRAM) chip is a memory chip which retains its contents indefinitely so long as power is maintained. By contrast, each of several blocks of bits in a dynamic RAM (DRAM) chip retains its contents for only a short time after it’s accessed for a read or write. In order to get a DRAM chip to store data for an extended period, each of the blocks of bits in that chip must be accessed regularly, so that the chip’s stored data is kept refreshed and valid. So long as this is done often enough, a DRAM chip will retain its contents indefinitely.

Don’t sweat the details here. The important point is this: for at least 4 out of every 72 cycles, the PC’s bus is given over to DRAM refresh and is not available to the 8088, as shown in Figure 4.5. That means that as much as 5.56% of the PC’s already inadequate bus capacity is lost. However, DRAM refresh doesn’t necessarily stop the 8088 for 4 cycles. The Execution Unit of the 8088 can keep processing while DRAM refresh is occurring, unless the EU needs to access memory. Consequently, DRAM refresh can slow code performance anywhere from 0% to 5.56% (and actually a bit more, as we’ll see shortly), depending on the extent to which DRAM refresh occupies cycles during which the 8088 would otherwise be accessing memory.

动态存储器和wait states都是等待,但是它们出现等待的原因不同。

Before we begin our discussion of dynamic RAM refresh, let’s step back for a moment to take an overall look at this lowest level of cycle-eaters. In truth, the distinctions between wait states and dynamic RAM refresh don’t much matter to a programmer. What is important is that you understand this: under certain circumstances devices on the PC bus can stop the 8088 for 1 or more cycles, making your code run more slowly than it seemingly should.

Unlike all the cycle-eaters we’ve encountered so far, wait states and dynamic RAM refresh are strictly external to the 8088, as shown in Figure 4.1. Adapters on the PC’s bus, such as video and memory cards, can insert wait states on any 8088 bus access, the idea being that they won’t be able to complete the access properly unless the access is stretched out. Likewise, the channel of the DMA controller dedicated to dynamic RAM refresh can request control of the bus at any time, although the 8088 must relinquish the bus before the DMA controller can take over. This means that your code can’t directly control wait states or dynamic RAM refresh. However, code can sometimes be designed to minimize the effects of these cycle-eaters, and even when the cycle-eaters slow your code without there being a thing in the world you can do about it, you’re still better off understanding that you’re losing performance and knowing why your code doesn’t run as fast as it’s supposed to than you were programming in ignorance.

Cycle-Eaters: A Summary

We’ve covered a great deal of sophisticated material in this chapter, so don’t feel bad if you haven’t understood everything you’ve read; it will all become clear as you read on. What’s really important is that you come away from this chapter understanding that:

- The 8-bit bus cycle-eater causes each access to a word-sized operand to be 4 cycles longer than an equivalent access to a byte-sized operand.

- The prefetch queue cycle-eater can cause instruction execution times to be as much as four times longer than the times specified in Appendix A.

- The DRAM refresh cycle-eater slows most PC code, with performance reductions ranging as high as 8.33%.

- The display adapter cycle-eater typically doubles and can more than triple the length of the standard 4-cycle access to display memory, with intensive display memory access suffering most.

This basic knowledge about cycle-eaters puts you in a good position to understand the results reported by the Zen timer, and that means that you’re well on your way to writing highperformance assembler code. We will put this knowledge to work throughout the remainder of The Zen of Assembly Language.

Avoid Memory!

We’ve come to the end of our discussion of memory addressing. Memory addressing on the 8088 is no trivial matter, is it? Now that we’ve familiarized ourselves with the registers and memory addressing capabilities of the 8088, we’ll start exploring the instruction set, a journey that will occupy most of the rest of this volume.

Before we leave the realm of memory addressing, let me repeat: avoid memory. Use the registers to the hilt; register-only instructions are shorter and faster. If you must access memory, try not to use mod-reg-rm addressing; the special memory-accessing instructions, such as the string instructions and xlat, are generally shorter and faster. When you do use mod-reg-rm addressing, try not to use displacements, especially 2-byte displacements.

Last but not least, choose your spots. Don’t waste time optimizing non-critical code; focus on loops and other chunks of code in which every cycle counts. Assembler programming is not some sort of game where the object is to save cycles and bytes blindly. Rather, the goal is a dual one: to produce whole programs that perform well and to produce those programs as quickly as possible. The key to doing that is knowing how to optimize code, and then doing so in time-critical code—and only in time-critical code.

8080指令集将永远存在于这个世界上

Today the need for 8080 source-level compatibility is long gone, but that 8080-oriented instruction set is with us still, and seems likely to survive well into the 21st century in the silicon of the 80386 and its successors. (Amazingly, every processor shown in Figure 3-5 provides full 8088 compatibility, and it’s a safe bet that future generations will be compatible as well. In fact, although it hasn’t happened as of this writing, it appears that some non-Intel manufacturers may build 8088-compatible subprocessors into their chips!)

The 8080 flavor of the 8088’s instruction set is both a curse and a blessing. It’s a curse because it limits the performance of average 8088 code, and a blessing because it provides great opportunity for assembler code to shine. In particular, the 8080-specific instructions occupy valuable space in the 8088 opcode set—arguably causing native 8088 code (as opposed to ported 8080 code) to be larger and slower than it would otherwise be—and that is, by-and-large, one of the less appealing aspects of the 8088. For the assembler programmer, however, the 8080-specific instructions can be an asset. Since those instructions are faster and more compact than their general-purpose counterparts, they can often be used to create significantly better code. Next, we’ll examine the 8080-specific instructions in detail.

优化是没有尽头的,你始终能节省那么几个指令周期

Code for almost any task can be implemented in many different ways, and can in the process usually be made faster than it currently is. It’s not always worth the cost in programming time and/or bytes to speed up code—you must pick your spots carefully, concentrating on loops and other time-critical code—but it can almost always be done. The key to improved performance lies in understanding exactly what the task at hand requires and understanding the context in which the code performs, and then matching that understanding to the resources of the PC.

My own experience is that no matter how many times I study a time-critical sequence of, say, 20-100 instructions, I can always save at least a few more cycles—and sometimes many more—by viewing the code differently and reworking it to match the capabilities of the 8088 more closely. That’s why way back in Chapter 2 I said that “optimize”was not a word to be used lightly. When programming in assembler for the PC, only fools and geniuses consider their code optimized. As for the rest of us… well, we’ll just have to keep working on our time-critical code, trying new approaches and timing the results, with the attitude that our code is good and getting better.

自修改代码几乎没有生存空间,JIT除外

“Frowned upon, eh?” you think. “Sounds like fertile ground for a little Zen programming, doesn’t it?” Yes, it does. Nonetheless, I don’t recommend that you use self-modifying code, at least not self-modifying code in the classic sense. Not because it’s frowned-upon, of course, but rather because I haven’t encountered any cases where in-line code, look-up tables, jump vectors, jumping through a register or some other 8088 technique didn’t serve just about as well as self-modifying code.

Self-modifying code has an additional strike against it in the form of the prefetch queue. If you modify an instruction byte after it’s been fetched by the Bus Interface Unit, it’s the original, unmodified byte that’s executed, since that’s the byte that the 8088 read. That’s particularly troublesome because the various members of the 8086 family have prefetch queues of differing lengths, so self-modifying code that works on the PC might not work at all on an AT or a Model 80. A branch always empties the prefetch queue and forces it to reload, but even that might not be true with future 8086-family processors.

“The key here is realizing that in assembler there’s no need for a clean separation between subroutines. If multiple subroutines end with the same instructions, they might as well share those instructions. Of course, performance will suffer a little from the extra branch all but one of the subroutines will have to make in order to reach the common code. Once again, we’ve acquired a new tool that has both costs and benefits; this time it’s a tool that saves bytes while expending cycles. Deciding when that’s a good tradeoff is your business, to be judged on a case by case basis. Sometimes this new tool is desirable, sometimes not… but either way, making that sort of decision properly is a key to good assembler code.”

既然8088即将被淘汰,我们为什么还要死磕8088指令集?(结合上面说的,8088将永存)

There are several reasons. Each by itself is probably ample reason to optimize for the 8088; together, they make a compelling argument for 8088-specific optimization. Briefly put, the reasons are:

- The 8088 is the lowest common denominator of the 8086 family for both compatibility and performance.

- The market for software that runs on the 8088 is enormous.

- The 8088 is the 8086-family processor for which optimization pays off most handsomely.

- The 8088 is the only 8086-family processor which comes in a single consistent system configuration—the IBM PC.

- The major 8088 optimizations work surprisingly well on the 80286 and 80386.

The 8088 is also the processor for which optimization pays off best. The slow memory access, too-small 8-bit bus, and widely varying instruction execution times of the 8088 mean that careful coding can produce stunning improvements in performance. Over the past few chapters we’ve seen that it’s possible to double and even triple the performance of already-tight 8088 assembler code. While the 80286 and 80386 certainly offer optimization possibilities, their superior overall performance results partly from eliminating some of the worst bottlenecks of the 8088, so it’s harder to save cycles by the bushel. Then, too, the major optimizations for the 8088—keep instructions short, use the registers, use string instructions, and the like—also serve well on the 80286 and 80386, so optimization for the 8088 results in code that is reasonably well optimized across the board.

And 80386 protected mode programming, my friend, is quite a different journey from the one we’ve been taking. While the 80386 in protected mode bears some resemblance to the 8088, the resemblance isn’t all that strong. The protected-mode 80386 is a wonderful processor to program, and a good topic—a terrific topic—for some book to cover in detail… but this is not that book.