Lessons Learned while Working on Large-Scale Server Software

http://ferd.ca/lessons-learned-while-working-on-large-scale-server-software.html

Of all the lessons I've learned, there is one that can summarize them all in 3 simple words: everything is terrible. This text is an attempt to recount some of the hard-earned lessons I have ended up learning, sometimes indirectly, but often personally. Everything is terrible, but our job still is to build something solid and usable on top of that everything. What we build adds to that 'everything', makes it bigger, more terrible.(简单地概括为3个词: everything is terrible. 但是即便如此我们依然需要在这个everything上面构建可靠可用的系统)

Existing systems come with all sorts of terrors; each time I touch something, I cause subtle ripples that disrupt the careful balance of all the elements holding it together. Each bug fixed opens the door to a bigger one, hidden deeper, and more violent.(系统组件之间存在涟漪效应,所以必须要平衡它们)

Writing new systems comes with an inescapable feeling of dread. I can imagine everything failing before it has been written, and feel sorry for the person who'll maintain it—possibly me.(构建新的系统会会有一种不可避免的恐惧,甚至在写代码之前就会感觉到失败,并且为每个维护这个系统的人感到抱歉)

That being said, here are fourteen lessons I've learned or live by in order to be more comfortable with the task at hand. I also recommend you read How Complex Systems Fail by Richard I. Cook. It's a much better list than mine.(另外推荐一篇文章 How Complex Systems Fail)

Plan for the worst

永远需要为出错的最坏情况做打算,这样即使出现问题你也不至于手足无措,因为你知道即使出现最坏情况也可以处理。

处理最坏情况的另外一个好处是,你可以知道如何处理系统中其他错误。处理这些错误只不过是处理最坏情况的一个优化而已。

如果你不理解系统如何出现故障,那么你就不理解系统如何工作。

Always have a plan for the worst case scenario for error conditions. What happens if all the databases are down? What if they're up but have lost all of their data?

Find a general solution for that. And by general solution, it can be as simple as automatically shutting down all operations and returning an error code. Maybe your clients should or will know how to cope with that, wait a bit, retry later. Maybe they'll have a contact number to call to talk to someone letting them know things will be alright, even if the sky is falling right now.

Once this is done, you know what's your bottom of the barrel. You know that if everything goes to hell, it won't be worse than that. This is a recomforting baseline. Any error condition you will not have seen coming, every operator error, every weird circumstances you'll have, it will at worst be as bad as this one.

Handle this worst case scenario and you've just figured out how to handle pretty much all errors in your system. It might be painful, but all other error recovery modes are just optimizations over this one. You do not understand how your system works if you do not understand how it fails.

The CAP Theorem is Real

详尽记录下系统设计实现方案。尽可能地让系统满足幂等性。

Do not forget it. The CAP Theorem is a good model to keep in mind. It's not exaustively listing everything that can go bad, but it forces you into making important decisions. Pick your poison, and stick to it.

Document the option you've taken, and if possible, have every bit of your system that can respect it do so. Idempotence is your best friend. It can be as simple as stamping every message with a recognizable ID that ensures the system will refuse to reprocess the same logical message twice, or it can be fancier (a 'diff' carries enough context to not be reapplied multiple times, for example). But having that property saves a lot of headaches.

The Fallacies of Distributed Computing are Real

分布式系统有许多陷阱(和需要问题需要考虑),所以尽可能地让系统不要分布式。

Do not forget it either. The eight fallacies of distributed computing will be what you live and die by. The network sucks, latency is unpredictable, bandwidth has a cost and limits, people may invade your network, things will move around, many teams or corporations will be in charge of various parts of your system (and each will have their own agenda), you'll have all kinds of devices, protocols, serialization formats, and some of them will be worse than others—likely the most used ones.

If you can avoid making parts of your system distributed, avoid it. It's leaving the comfort of your home to step into a rain of fire.

If you have to make parts of your system distributed, please, think about it. Hard. Know what that means, how it can fail, die, look healthy (but still be failing), and how it can recover. There's nothing more dangerous than someone going for a stroll over the network without knowing what it entails.

Back-Pressure or Load-shedding: pick one.

如果系统负载过高的话,为了防止导致系统故障,有两种方式可以解决:back-pressure(回推压力)或者是load-shedding(分摊负载)

I've written and spoken a lot about this one.

Sooner or later, your system will be overloaded. You have two options: do you stop people from inputting stuff in the system, or do you shed load. Those are inescapable choices, where inaction leads to system failure. System failure means you both stop taking input and lose what was going through the system.

Pick one and prevent (some) losses. Pick one and guide your entire strategy towards optimization and staying away from your accident boundary.

Debugging is a Science

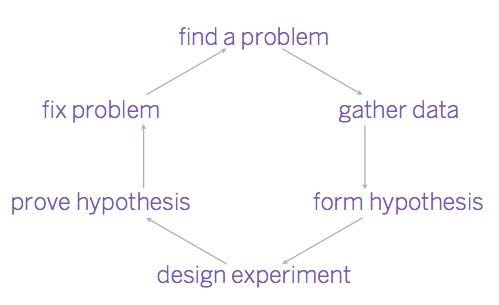

In Programming Forth (Stephen Pelc, 2011), the author says "Debugging isn't an art, it's a science!" and provides the following (reproduced) diagram:

By far, the easiest bit is 'find a problem'. The difficult bit is to form the right hypothesis that will let you design a proper experiment and prove your fix works. It's especially true of Heisenbugs that ruin your life by disappearing as you observe them.(发现问题非常容易,难的是如果形成正确假设,然后来设计合理的实验,证明fix是有效的)

Embrace systems and platforms that you can dig into. The hard bugs are those you will not have seen coming, and therefore those that have nearly no instrumentation or metrics around them; otherwise, they'd be caught early and not be left to fester until other things mix in with them to create a deadly chimera of failure.(复杂bug通常都是你所不能预见的,所以也没有任何指令或者是指标来发现它们,否则这些bug很容易被尽早发现)

It's no secret I'm a fan of Erlang where I can trace everything and inspect memory live without stopping the system. I swear by these tools more than I'd like to need to, and I frankly can't imagine the pain of investigating without them anymore. (Erlang系统允许在线来追踪所有对象以及查看内存,这对于调试系统非常有帮助)

These cut down the debugging loop so much I wish people who never had such tools to assist them could try them on their systems. If you're dealing with the network and know tcpdump and wireshark, imagine the same thing, but for your entire programs. It's the best analogy I can come up with.(正确地掌握工具大幅度地减少整个debug过程。比如如果处理网络问题,那么最好会使用tcpdump/wireshark)

Postel's Law is Hard.

Postel's Law says "Be conservative in what you send, be liberal in what you accept". There is a good interpretation of it that makes a lot of sense, but the colloquial usage of it tends to mean "send good data, try to accept garbage".

That latter form is hogwash. Always start your implementations as strict as possible. It's much harder to respect the lenient version of Postel's Law without accidentally corrupting data than it is to just implement the specification strictly and end up never corrupting anything.

Don't trust the network.

网络方面坑多多:对待localhost和remotehost处理方式是不同的;内核也会有罕见的TCP bugs;甚至某些行为知道在特定条件下面才会出现。所以对待网络问题更应该使用保守眼光来看待。

This is a bit redundant now with mentions of the CAP theorem and the fallacies of distributed computing. But really, just don't trust the network. The network owes you nothing, and it doesn't care about your feelings. It doesn't deserve your trust.

Operating systems will react differently to connections that are made over your localhost (or loopback interface) than those from remote hosts. Your tests may mean nothing. Some kernels will have tricky rare TCP bugs. Some behaviours will only show up when discussing with specific hosts doing specific things with specific configurations and never show up again (or show up all the time). Asymmetric netsplits are real (and they even kill Raft very bad).

The network is a necessary evil, not a place to expand to for fun. Respect End-to-End principles if you want your life to be easier. (所谓end-to-end原则强调尽可能地让high-level code来处理异常情况。只有当low-level code处理异常情况代价很小并且明确地知道如何操作时,才让low-level code来做)

Et tu, System? (And you, System?)

随着时间推移,系统内部熵会不断增加,最终会变得难以修改扩展以及满足需求。(所以定期需要对系统审查和重构)

系统成功很大一部分也和运维相关。如果团队缺乏这个系统运维实践的话,那么这个系统很快就会不可用。

The pieces of your infrastructure you trust the most will eventually be your most painful ones. Someone will inevitably trust them so much they'll become 'magic' to your (or another) team. As everyone learns to trust it without ever touching it, it starts to rot and suffer under pressure. You end up having to do difficult (sometimes impossible) scaling operations on components that are now both legacy and critical. Worse, changes will be time-boxed as product development becomes tied to its scaling and performance.

A huge part of a system's success is tied to its operators. Without enough practice, they might just become the riskiest part of the system. And here comes the sense of dread.

Crash Early, Crash Often

有问题,别闷着

When you're not sure about how to handle an error, let it crash. Violent failures on 1/Nth of your system early on is far better than silent corruption in 100% of it over a long period of time. Errors that declare themselves loudly and early are easy to spot, and easy to thwart. Errors that you notice have been slowly destroying your system from the inside over the course of days, weeks, or months are what is truly painful.

Deploys Fix Bugs, Cause Failures

Installing and deploying new software is a great way to introduce all kinds of new variables in your system and bring it down. The bigger the deploy, the scarier.

In my experience, a major code deployment that goes terrible causes shame. A major deployment that has minor issues is par for the course. A major deployment that goes well is terrifying because we all make mistakes, and if they weren't violent, they might just be the silent kind that takes a long time to detect.

Long Running Systems Have Their Own Bugs

持续部署通常需要经常重启服务,那么服务中一些需要长时间运行才会暴露的错误便不容易被发现。这也意味着这些bug很可能就在你度假或者是陷入新项目时候出现,而此时又不太可能立即进行部署,进退两难。

Continuous deployment (with rolling upgrades) is standard practice these days, to varying degrees. Restarting nodes frequently means that all the funny behaviours, corruptions, and low-probability events that take a long time to develop and show themselves will remain hidden.

It also means that they'll only show up when everyone's on vacation, during the holidays, or whenever everyone is knee-deep in new project development and new deploys aren't occuring for an extended period of time. This means not deploying changes is also a great way to make your systems go bad.

Be Ready for a Total Restart

时刻准备好完全重启(就怕某一天完全重启之后系统就再也起不来了)

Be ready to restart the entire system from a blank slate, under load. If you can't do it, the day someone or something takes the whole thing down accidentally (or intentionally!), you'll be unable to bring it back up.

This can be the difference between less than one hour of downtime with a quick turnaround, and spending 15 hours trying to bring things back up unsuccessfully.

There's more Global stuff than variables

Global variables are one kind of thing that can break your programs by spookily changing things at a distance. More insidious are entrenched implicit design decisions. Sometimes, an accidental (or at least non-explicit) technical decision has been made and relied on by other components.(全局变量会因为在其他地方更改而导致程序崩溃,所以我们会尽量避免。可是在系统设计时候,我们会无意引入其他组件依赖的全局组件)

Think of a case where an integer is used as an ID for some events or entries in a system. You change it to a UUID (because that reduces bottlenecks or conflicts and you can split up your system), and suddenly 3 unrelated subsystems break because somehow they used a 'sort' function on the IDs to determine monotonic increments and provide time order to our entries. Woops. All of a sudden, a seemingly small change has to be reverted and cannot be enacted until a parallel mechanism is developed to provide the same feature that was otherwise implicit.(比如我们从自增ID切换到UUID)

Refactoring of large systems, particularly legacy systems, is fraught with peril because there have been many such decisions, made by both smart and distracted people, that end up acting as invisible glue to large parts of everything you stand on. Refactoring can only truly begin once you've actually learned what a piece of code or some data structure did, the unique properties for which they were written or chosen. Anything else is setting yourself up for failure.(重构大的系统,尤其是遗留系统,通常是非常危险的事情,因为我们很容易忽视和其他系统组件交互的隐含假设)

It's all about people

一切都是和人相关的,所以必须不断地把这个系统方面的知识传递给团队更多的人,同时要准备有人会犯错。最终系统会一直运行于半故障的状态。

Humans are the lynchpin holding things together. Systems will live and die by them. Hard-earned lessons about making systems stay alive, operating them, and learning how they should behave to quickly spot what's abnormal take time to develop, and is usually held by humans.

This kind of knowledge usually remains embedded within the teams that develop it, and tends to die when individuals leave or change roles. When new members join the team, it gets transmitted informally, over incident simulations, code reviews, and other similar practices, but never in a really persistent manner. Being aware of that and building channels for more persistent information is crucial.

It also means that when building systems, you should not assume that operators will do things correctly. Expect failure from people. Try to think about tools you can give them to undo their mistakes, because they will happen sooner or later. Have some dread. Be understanding. Know things won't be perfect.

In the end that's how all systems live and die: in a perpetual state of partial failure. Major failures is just what happens when many of them occur at a given time. A system that is 100% healthy is a system that probably needs better monitoring, because that's not normal; it's worrisome.