Lessons Learned From Reading Postmortems

Table of Contents

http://danluu.com/postmortem-lessons/

1. Error Handling

Proper error handling code is hard. Bugs in error handling code are a major cause of bad problems. This means that the probability of having sequential bugs, where an error causes buggy error handling code to run, isn’t just the independent probabilities of the individual errors multiplied. It’s common to have cascading failures cause a serious outage. # 错误处理中的bugs经常造成级联错误引起故障.

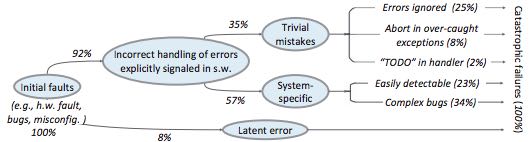

For more on this, Ding Yuan et al. have a great paper and talk: Simple Testing Can Prevent Most Critical Failures: An Analysis of Production Failures in Distributed Data-Intensive Systems. The paper is basically what it says on the tin. The authors define a critical failure as something that can take down a whole cluster or cause data corruption, and then look at a couple hundred bugs in Cassandra, HBase, HDFS, MapReduce, and Redis, to find 48 critical failures. They then look at the causes of those failures and find that most bugs were due to bad error handling. 92% of those failures are actually from errors that are handled incorrectly. # 论文作者将关键失效定义为集群宕掉或者是数据损坏. 然后从许多开源软件上百个bugs中找出48个严重失效. 他们发现其中92%是因为错误处理中bugs造成的.

Drilling down further, 25% of bugs are from simply ignoring an error, 8% are from catching the wrong exception, 2% are from incomplete TODOs, and another 23% are “easily detectable”, which are defined as cases where “the error handling logic of a non-fatal error was so wrong that any statement coverage testing or more careful code reviews by the developers would have caught the bugs”. # 其中23%的"easily detectable"是指non-fatal error的处理, 而这些处理中的bug完全可以通过简单的覆盖测试或者是严格的code review来发现.

2. Configuration

Configuration bugs, not code bugs, are the most common cause I’ve seen of really bad outages. When I looked at publicly available postmortems, searching for “global outage postmortem” returned about 50% outages caused by configuration changes. Publicly available postmortems aren’t a representative sample of all outages, but a random sampling of postmortem databases also reveals that config changes are responsible for a disproportionate fraction of extremely bad outages. As with error handling, I’m often told that it’s obvious that config changes are scary, but it’s not so obvious that most companies test and stage config changes like they do code changes. # 从公开的postmortems可以发现近50%故障中断是因为配置变化. 就像错误处理一样, 虽然大部分公司虽然觉得配置变化很重要, 但是却很少像代码变化一样来测试和演练.

Except in extreme emergencies, risky code changes are basically never simultaneously pushed out to all machines because of the risk of taking down a service company-wide. But it seems that every company has to learn the hard way that seemingly benign config changes can also cause a company-wide service outage. For example, this was the cause of the infamous November 2014 Azure outage. I don’t mean to pick on MS here; their major competitors have also had serious outages for similar reasons, and they’ve all put processes into place to reduce the risk of that sort of outage happening again. # 除非特殊情况, 否则代码变化不会立刻被部署到所有节点上, 以减少所有服务同时挂掉的风险. 但是大部分公司却敢于直接将配置变化部署到线上.

I don’t mean to pick on large cloud companies, either. If anything, the situation there is better than at most startups, even very well funded ones. Most of the “unicorn” startups that I know of don’t have a proper testing/staging environment that lets them test risky config changes. I can understand why – it’s often hard to set up a good QA environment that mirrors prod well enough that config changes can get tested, and like driving without a seatbelt, nothing bad happens the vast majority of the time. If I had to make my own seatbelt before driving my car, I might not drive with a seatbelt either. Then again, if driving without a seatbelt were as scary as making config change, I might consider it. # 许多创业公司包括unicorn公司都没有合适的测试演练环境来测试配置变化.

(这就好像是汽车安全带. 如果我必须在上车之前, 发现没有安全带而必须自己做一条的话, 那么我很有可能就干脆不系安全带. 因为开车不系上安全带, 大部分时候没有任何问题. 但是话说回来, 如果我发现不系安全带很容易出事故的话, 那么我很可能考虑自己做一条安全带)

3. Monitoring / Alerting

The lack of proper monitor is never the sole cause of a problem, but it’s often a serious contributing factor. As is the case for human errors, these seem underrepresented in public postmortems. When I talk to folks at other companies about their worst near disasters, a large fraction of them come from not having the right sort of alerting set up. They’re often saved having a disaster bad enough to require a public postmortem by some sort of ops heroism, but heroism isn’t a scalable solution. # 合理的监控和报警

Sometimes, those near disasters are caused by subtle coding bugs, which is understandable. But more often, it’s due to blatant process bugs, like not having a clear escalation path for an entire class of failures, causing the wrong team to debug an issue for half a day, or not having a backup oncall, causing a system to lose or corrupt data for hours before anyone notices when (inevitably) the oncall person doesn’t notice that something’s going wrong. # 正确的处理流程, 指出某类故障的escalation path(谁应该处理, 是否应该汇报上级).

The Northeast blackout of 2003 is a great example of this. It could have been a minor outage, or even just a minor service degredation, but (among other things) a series of missed alerts caused it to become one of the worst power outages ever.