LeanStore: In-Memory Data Management Beyond Main Memory

Table of Contents

LeanStore: In-Memory Data Management Beyond Main Memory

https://db.in.tum.de/~leis/papers/leanstore.pdf

这篇文章发表2018年(https://github.com/leanstore/leanstore),在内存数据库的基础上,增加了对disk的支持。之后把这些技术都移植到了Umbra(2020, https://umbra-db.com/)这个系统上,所以会发现其实umbra上的很多技术其实和这个这里很像,所以其实leanstore应该是这些技术的源头。Umbra和Leanstore差别主要在于前者是OLAP后者是OLTP,不过两个都是TUM出来的东西。

1. introduction

使用buffer management来管理page的方式太低效了,每次都需要根据page id去hash table里面寻找对应的page. 最好的方式还是直接使用指针,现在许多内存关系数据库也尽量不使用buffer management的方式。

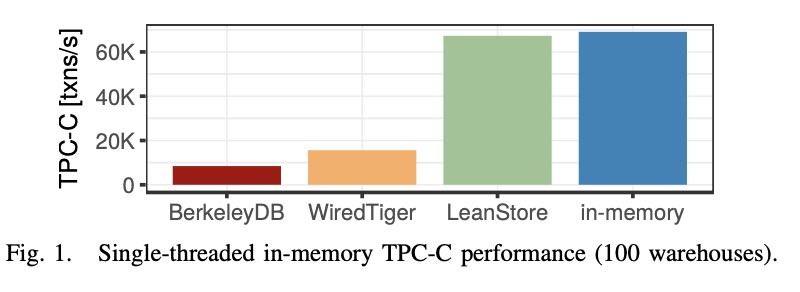

While this design succeeds in minimizing the number of I/O operations, it incurs a large overhead for in-memory workloads, which are increasingly common. In the canonical buffer pool implementation [1], each page access requires a hash table lookup in order to translate a logical page identifier into an in-memory pointer. Even worse, in typical implementations the data structures involved are synchronized using multiple latches, which does not scale on modern multi-core CPUs. As Fig. 1 shows, traditional buffer manager implementations like BerkeleyDB or WiredTiger therefore only achieve a fraction of the TPC-C performance of an in-memory B-tree.

This is why main-memory database systems like H-Store [2], Hekaton [3], HANA [4], HyPer [5], or Silo [6] eschew buffer management altogether. Relations as well as indexes are directly stored in main memory and virtual memory pointers are used instead of page identifiers. This approach is certainly efficient. However, as data sizes grow, asking users to buy more RAM or throw away data is not a viable solution. Scaling-out an in- memory database can be an option, but has downsides including hardware and administration cost. For these reasons, at some point of any main-memory system’s evolution, its designers have to implement support for very large data sets.

下面就是传统的使用page id管理基于磁盘数据库和直接使用指针管理内存的数据库差距。

2. related work

目前大部分内存数据库的实现方法都是避开buffer management. 另外一个比较大的开销就是追踪page的使用来做淘汰,这个leanstore也有一个方法来解决。

Buffer management is the foundational component in the traditional database architecture [13]. In the classical design, all data structures are stored on fixed-size pages in a translation- free manner (no marshalling/unmarshalling). The rest of the system uses a simple interface that hides the complexities of the I/O buffering mechanism and provides a global replacement strategy across all data structures. Runtime function calls to pinPage/unpinPage provide the information for deciding which pages need to be kept in RAM and which can be evicted to external memory (based on a replacement strategy like Least-Recently-Used or Second Chance). This elegant design is one of the pillars of classical database systems. It was also shown, however, that for transactional, fully memory-resident workloads a typical buffer manager is the biggest source of inefficiency [14].

One of the defining characteristics of main-memory databases is that they do not have a buffer manager. Memory is instead allocated in variable-sized chunks as needed and data structures use virtual memory pointers directly instead of page identifiers. To support data sets larger than RAM, some main- memory database systems implement a separate mechanism that classifies tuples as either “hot” or “cold”. Hot tuples are kept in the efficient in-memory database, and cold tuples are stored on disk or SSD (usually in a completely different storage format). Ma et al. [15] and Zhang et al. [16] survey and evaluate some of the important design decisions. In the following we (briefly) describe the major approaches.

避开buffer management的方法大致有下面这些:

- H-Store. index/data分开存储,但是其实index也必须存储在内存中

- MS Siberia. index/data分开存储,index只照顾到hot tuples. 但是文章吐糟这种复杂程度太高了。 `The Siberia approach, however, suffers from high complexity (multiple offline processes with many parameters, two independent storage managers), which may have prevented its widespread adoption. `

- 直接使用linux mmap来做swapping. 缺点就是许多东西不太好控制,性能以及事务正确性都不好控制。 `The disadvantage is that the database system loses control over page eviction, which virtually precludes in-place updates and full-blown ARIES-style recovery.` 目前就已知的就是MonetDB使用mmap来比较好。

- 使用hardware-assited access tracking. 写个linux driver配合mmap使用,其中linux driver可以用来控制。本质上就是把应用层的逻辑放在了内核层,复杂而且好像没啥必要。

- Bw-tree. 可以在读取的时候将写缓存在deltas下面,但是读取的时候还是需要遍历这些deltas. 同样延续MS的风格:复杂。

3. building blocks

3.1. pointer swizzling

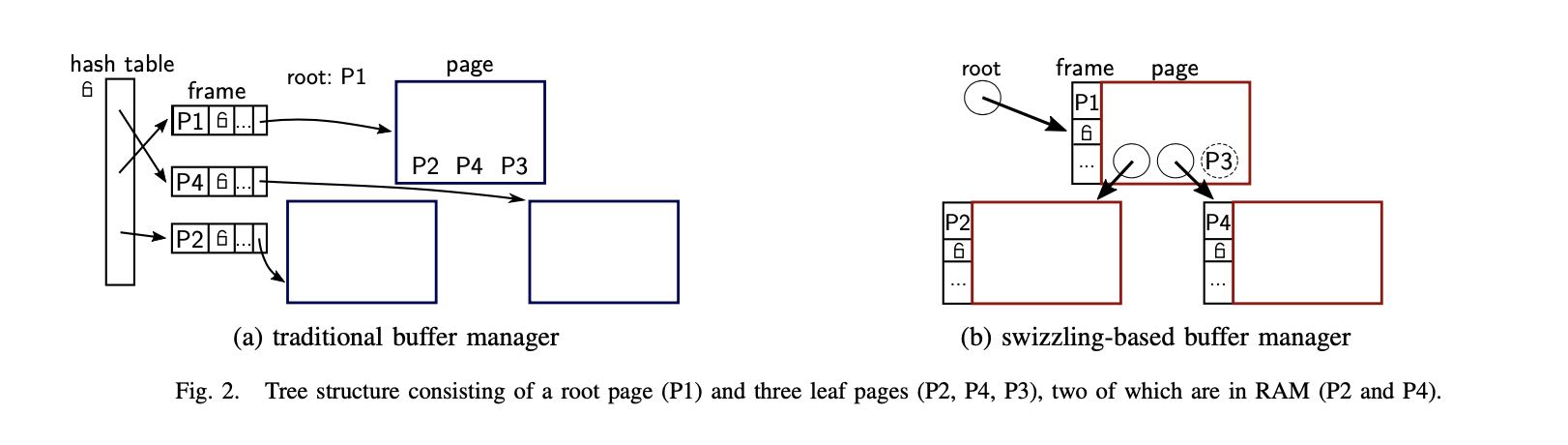

这个就是在pointer内容里面做个标记,在内存的状态叫做 "swizzled", 在磁盘状态叫做 "unswizzled".

This technique is called pointer swizzling [28] and has been common in object databases [29], [26]. A reference containing an in-memory pointer is called swizzled, one that stores an on- disk page identifier is called unswizzled. Note that even swizzled pages have logical page identifiers, which are, however, only stored in their buffer frames instead of their references.

3.2. efficient page replacement

追踪page使用成本比较高,leanstore采用了另外一种办法:

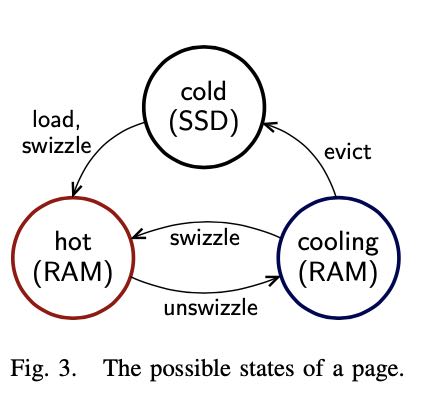

- 随机将一些page标记成为cooling状态,这些状态接下来随时会被unswizzled.

- 如果在cooling状态的话发生了访问的话,那么就挪到hot状态,并且有一段时间可以避免cooling状态。

- 如果没有访问的话,那么就会被刷新到ssd上。

The main mechanism of our replacement strategy is to spec- ulatively unswizzle a page reference, but without immediately evicting the corresponding page. If the system accidentally unswizzled a frequently-accessed page, this page will be quickly swizzled again—without incurring any disk I/O. Thus, similar to the Second Chance replacement strategy, a speculatively unswizzled page will have a grace period before it is evicted. Because of this grace period, a very simple (and therefore low- overhead) strategy for picking candidate pages can be used: We simply pick a random page in the pool.

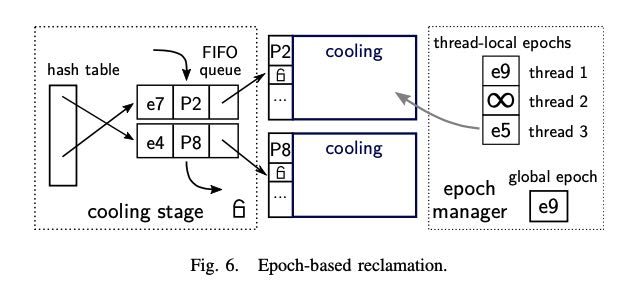

We call the state of pages that are unswizzled but are still in main memory cooling. At any point in time we keep a certain percentage of pages (e.g., 10%) in this state. The pages in the cooling state are organized in a FIFO queue. Over time, pages move further down the queue and are evicted if they reach the end of the queue. Accessing a page in the cooling state will, however, prevent eviction as it will cause the page to be removed from the FIFO queue and the page to be swizzled.

3.3. scalable sync

通常page同步需要在上面增加一个pin counter标记:表示这个page被多少threads使用。问题在于这样每次page使用的话,都会产生write,在并发环境下面对于cpu cache不利。leanstore使用的是类似linux rcu回收资源的机制:有个global epoch, 每个thread持有锁之前会去申请一个local epoch, 只有当某个资源的epoch低于所有的thread min epoch的时候,这个资源才可以被回收。

As a general rule, programs that frequently write to memory locations accessed by multiple threads do not scale. LeanStore is therefore carefully engineered to avoid such writes as much as possible by using three techniques: First, pointer swizzling avoids the overhead and scalability problems of latching the translation hash table. Second, instead of preventing page eviction by incrementing per-page pinning counters, we use an epoch-based technique that avoids writing to each accessed page. Third, LeanStore provides a set of optimistic, timestamp- based primitives [31], [32], [33] that can be used by buffer- managed data structures to radically reduce the number of latch acquisitions. Together, these techniques (described in more detail in Section IV-F and Section IV-G) form a general frame- work for efficiently synchronizing arbitrary buffer-managed data structures. In LeanStore, lookups on swizzled pages do not acquire any latches at all, while insert/update/delete operations usually only acquire a single latch on the leaf node (unless a split/merge occurs). As a result, performance-critical, in- memory operations are highly scalable.

4. leanstore

4.1. data structutre

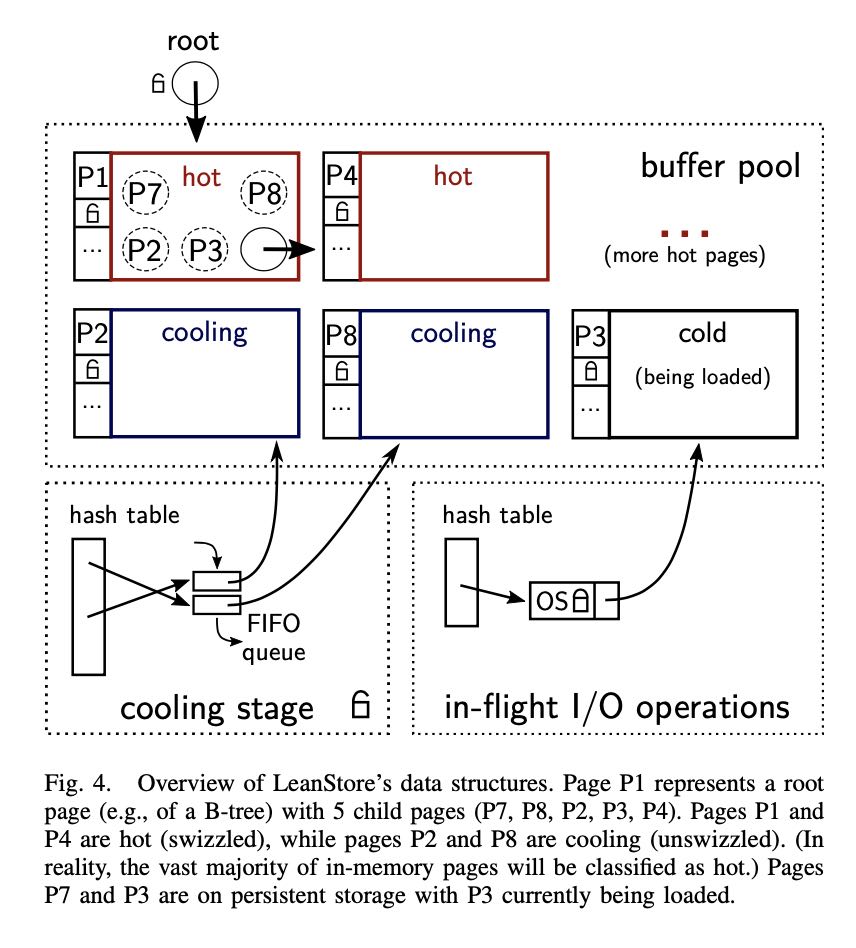

In a traditional buffer manager, the state of the buffer pool is represented by a hash table that maps page identifiers to buffer frames. Frames contain a variety of “housekeeping” information, including (1) the memory pointer to the content of the page, (2) the state required by the replacement strategy (e.g., the LRU list or the Second Chance bit), and (3) information regarding the state of the page on disk (e.g., dirty flag, whether the page is being loaded from disk). These points correspond to 3 different functions that have to be implemented by any buffer manager, namely (1) determining whether a page is in the buffer pool (and, if necessary, page translation), (2) deciding which pages should be in main memory, and (3) management of in-flight I/O operations. LeanStore requires similar information, but for performance reasons, it uses 3 separate, customized data structures. The upper half of Fig. 4 shows that a traditional page translation table is not needed because its state is embedded in the buffer-managed data structures itself. The information for implementing the replacement strategy is moved into a separate structure, which is called cooling stage and is illustrated in the lower-left corner of Fig. 4. Finally, in-flight I/O operations are managed in yet another structure shown in the lower-right corner of Fig. 4.

4.2. swizzling details

leanstore实现swaizzling pointer有几个重要约束:

- 指向一个page的指针叫做 `swip`

- 每个page只有一个owning `swip` . 所有page被组织成为树状结构,一个page只能被另外一个page所引用到。

- 只有children都被unswizzled了,父节点才能被unswizzled. 这个可以修改unswizzled逻辑,如果有children还处于swizzled的话,那么使用children节点被切换出去。

4.3. cooling stage

大约将10%的pages标记为cooling page.

The cooling stage is only used when the free pages in the buffer pool are running out. From that moment on, the buffer manager starts to keep a random subset of pages (e.g., 10% of the total pool size) in the cooling state. Most of the in-memory pages will remain in the hot state. Accessing them has very little overhead compared to a pure in-memory system, namely checking one bit of the swip.

将标记工作放在前台线程,并且只有一个global latch来保护cooling stage.

Moving pages into the cooling stage could either be done (1) asynchronously by background threads or (2) synchronously by worker threads that access the buffer pool. We use the second option in order to avoid the risk of background threads being too slow. Whenever a thread requests a new, empty page or swizzles a page, it will check if the percentage of cooling pages is below a threshold and will unswizzle a page if necessary.

Our implementation uses a single latch to protect the data structures of the cooling stage. While global latches often become scalability bottlenecks, in this particular case, there is no performance problem. The latch is only required on the cold path, when I/O operations are necessary. Those are orders of magnitude more expensive than a latch acquisition and acquire coarse-grained OS-internal locks anyway. Thus the global latch is fine for both in-memory and I/O-dominated workloads.

4.4. input/output

这些好像解决的问题是如何协调多个IO请求去加载同一个page. 首先把这个page放在hash table里面,拿到自己的mutex之后就可以释放global latch然后开始读取,完成之后释放自己的mutex. 这样读取阶段如果还有线程要去load page的时候,发现有mutex的话,就可以避免重复load.

Like traditional buffer managers, we therefore manage and serialize in-flight I/O operations explicitly. As Fig. 4 (lower- right corner) illustrates, we maintain a hash table for all pages currently being loaded from disk (P3 in the figure). The hash table maps page identifiers to I/O frames, which contain an operating system mutex and a pointer to a newly allocated page. A thread that triggers a load first acquires a global latch, creates an I/O frame, and acquires its mutex. It then releases the global latch and loads the page using a blocking system call (e.g., pread on Unix). Other threads will find the existing I/O frame and block on its mutex until the first thread finishes the read operation.

We currently use the same latch to protect both the cooling stage and the I/O component. This simplifies the implemen- tation considerably. It is important to note, however, that this latch is released before doing any I/O system calls. This enables concurrent I/O operations, which are crucial for good performance with SSDs. Also let us re-emphasize that this global latch is not a scalability bottleneck, because—even with fast SSDs—an I/O operation is still much more expensive than the latch acquisition.

4.5. optimistic latches

The first important technique is to replace the conventional per-page latches with optimistic latches [31], [32], [33]. Inter- nally, these latches have an update counter that is incremented after every modification. Readers can proceed without acquiring any latches, but validate their reads using the version counters instead (similar to optimistic concurrency control). The actual synchronization protocol is data-structure specific and different variants can be implemented based on optimistic latches. One possible technique is Optimistic Lock Coupling [33], which ensures consistent reads in tree data structures without physically acquiring any latches during traversal. Optimistic Lock Coupling has been shown to be good at synchronizing the adaptive radix tree [35], [33] and B-tree [36]. In this scheme, writers usually only acquire one latch for the page that is modified, and only structure modification operations (e.g., splits) latch multiple pages.

4.6. epoch-based reclamation

检查一些page是否可以被evict出去而没有被使用,使用类似RCU里面的epoch-based回收算法。大致思想就是维护global epoch和threead-local epochs. thread local epochs访问之前会使用global epoch, 所有内存被放置到cooling阶段也会使用global epoch. 然后这个global epoch是会不断增加的。要判断某个page是否依然被使用,只需要判断threads所有的epoch最小值就行:如果最小值依然大于page epoch的话,那么就认为可以释放掉而没有被引用。

With optimistic latches, pages that are being read are neither latched nor pinned. This may cause problems if some thread wants to evict or delete a page while another thread is still reading the page. To solve this problem, we adopt an epoch- based mechanism, which is often used to implement memory reclamation in latch-free data structures [6], [32], [23].

global epoch增加频率和所有的页面数量有关系:太快的话会造成cpu cache invalidation, 太慢的话会导致某些页面没有办法回收。

Note that incrementing the global epoch very frequently may result in unnecessary cache invalidations in all cores, whereas very infrequent increments may prevent unswizzled pages from being reclaimed in a timely fashion. Therefore, the frequency of global epoch increments should be proportional to the number of pages deleted/evicted but should be lower by a constant factor (e.g., 100).

另外一个影响回收的问题就是thread local epoch更新太慢:比如large scan table的话会让某个thread执行太长时间,期间的话epoch就不会发生任何变化。解决办法就是将large operation拆分成为多个阶段,每个阶段的话重新去加载global epoch. 我也不知道里面是否有什么潜在的一致性问题,但是应该都可以解决。

To make epochs robust, threads should exit their epoch frequently, because any thread that holds onto its epoch for too long can completely stop page eviction and reclamation. For example, it might be disastrous to perform a large full table scan while staying in the same local epoch. Therefore, we break large operations like table scans into smaller operations, for each of which we acquire and release the epoch. We also ensure that I/O operations, which may take a fairly long time, are never performed while holding on to an epoch. This is implemented as follows: If a page fault occurs, the faulting thread (1) unlocks all page locks, (2) exits the epoch, and (3) executes an I/O operation. Once the I/O request finishes, we trigger a restart of the current data structure operation by throwing a C++ exception. Each data structure operation installs an exception handler that restarts the operation from scratch (i.e., it enters the current global epoch and re-traverses the tree). This simple and robust approach works well for two reasons: First, in-memory operations are very cheap in comparison with I/O. Second, large logical operations (e.g., a large scan) are broken down into many small operations; after a restart only a small amount of work has to be repeated.