From Cloud Computing to Sky Computing

Table of Contents

1. introduction

名字稍微有点那啥,但是看完文章后觉得这个Sky Computing也还挺合适的,Sky Computing目的就是要将Cloud Computing Services结合起来,可以在不同的Cloud Vendors之间选择计算放在什么地方,存储在什么地方。

其实现在有许多公司在做Multi Cloud Services的抽象,不过最终service只能运行在一个cloud vendors上面,像这样整合多云的文章好像之前还没有。目前也有许多OSS Cloud Services的公司,可以将OSS产品可以无差异(或者是差异化很小地)在多个云上跑,这些可以作为Sky Computing的基础。

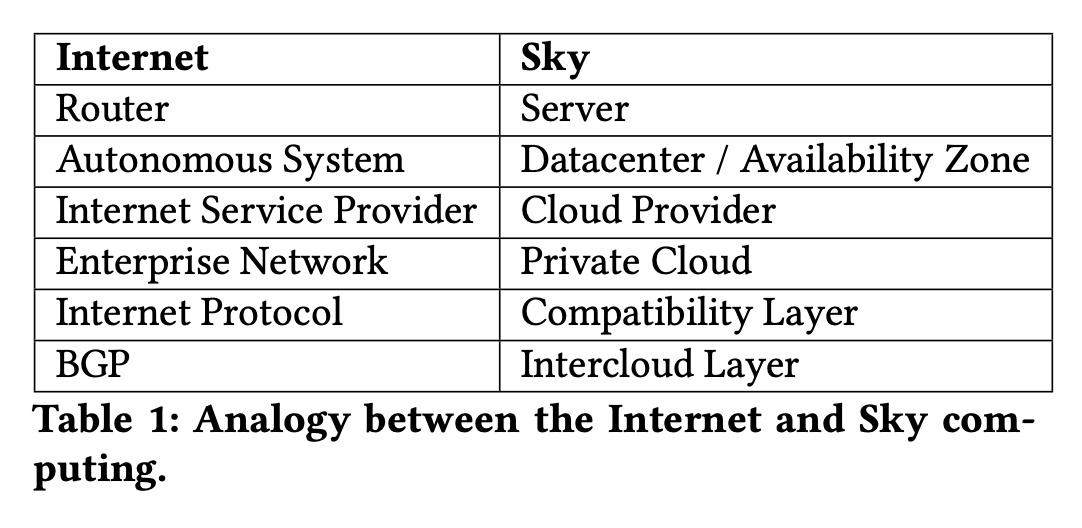

作者拿Internet的历史来说明网络技术和服务商是如何结合在一起的:

- IP技术被用于在不同的网络之间相互通信

- BGP技术用于在不同的AS之间做packet routing.

- ISP之间达成了如何对packet进行计费结算.

如果把这个过程抽象出来的话就是下面这样, 可能Sky Computing也会是这样的过程

Thus, there were three key design decisions that allowed the Internet to provide a uniform interface to a huge in- frastructure made out of heterogeneous technologies (from Ethernet to ATM to wireless) and competing companies. The first is a “compatibility” layer that masks technological het- erogeneity. The second is interdomain routing that glues the Internet together, making it appear as one network to end users. The third is a set of economic agreements, forming what we will call a “peering” layer, that allow competing networks to collaborate in creating a uniform network.

We contend that the three design issues the Internet had to address are exactly the pieces needed to create Sky comput- ing out of our current set of clouds. We need a compatibility layer to mask low-level technical differences, an intercloud layer to route jobs to the right cloud, and a peering layer that allows clouds to have agreements with each other about how to exchange services. In the next three sections we describe these layers in more detail. We then conclude by speculating about the future.

2. compatibility layer

这层是不同Cloud Vendors上的兼容层,目前看起来可以使用OSS来解决。目前在各种stack上都有OSS的实现,而OSS在不同平台上提供的都是相同的能力,这样可以比较好地屏蔽掉cloud vendors的差异。

These OSS projects exist all levels of the software stack, in- cluding operating systems (Linux), cluster resource managers (Kubernetes [12], Apache Mesos [31]), application packaging (Docker [10]), databases (MySQL [15], Postgres [17]), big data execution engines (Apache Spark [42], Apache Hadoop [41]), streaming engines (Apache Flink [26], Apache Spark [42], Apache Kafka [5]), distributed query engines and databases (Cassandra [4], MongoDB [14], Presto [18], SparkSQL [22], Redis [19]), machine learning libraries (PyTorch [37], Ten- sorflow [24], MXNet [27], MLFlow [13], Horovod [40], Ray RLlib [33]), and general distributed frameworks (Ray [36], Erlang [25], Akka [1]).

Furthermore, a plethora of companies founded by OSS creators have emerged to provide hosted services on mul- tiple clouds. Example are Cloudera (Apache Hadoop), Con- fluent (Apache Kafka), MongoDB, Redis Labs, HashiCorp (Terraform, Consul), Datastax (Cassandra), and Databricks (Apache Spark, MLFlow, and Delta). These developments make it relatively easy for enterprises to switch from one cloud to another if their applications are using one of these multi-cloud OSS-based offerings.

The compatibility layer could be constructed out of some set of these OSS solutions. Indeed, there are already efforts underway to consolidate different OSS components in a sin- gle coherent platform. One example is Cloud Foundry [9], an open source multi-cloud application platform that supports all major cloud providers, as well as on-premise clusters. Another example is RedHat’s OpenShift [16], a kubernetes- based platform for multi-cloud and on-premise deployments.

While OSS provides solutions at most layers in the soft- ware stack, the one glaring gap is the storage layer. Every cloud provider has its own version of proprietary highly- scalable storage. Examples are AWS’ S3 [2], Microsoft’s Azure Blob Storage [7] and Google’s Cloud Storage [11]. This be- ing said, there are already several solutions providing S3 compatibility APIs for Azure’s Blob Storage and Google’s Cloud Storage, such as S3Proxy [20] and Scality [21]. Some cloud providers offer their own S3 compatibility APIs to help customers transition from AWS to their own cloud. In what follows, we assume that the storage API provided by the compatibility layer allows reading data across clouds.

3. intercloud layer

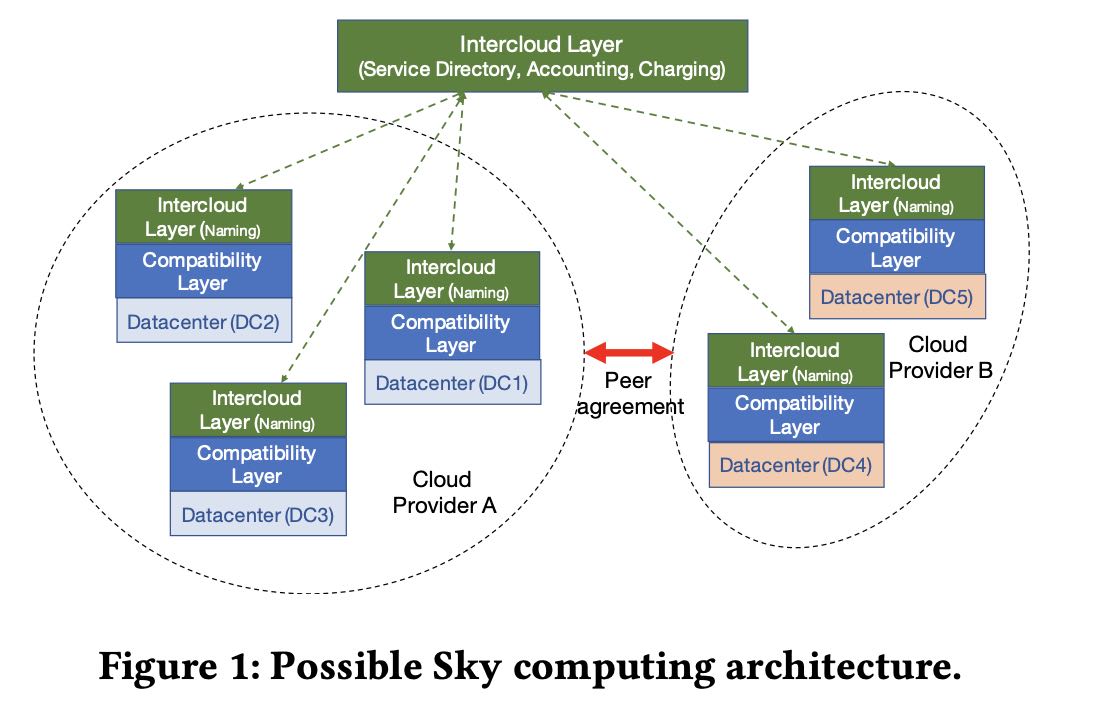

用户可以根据策略在多个云之间提交任务(这里暂时不考虑数据存储问题),看上去大概需要的能力有点类似于mesos/k8s这样的资源管理系统。

The intercloud layer must allow users to specify policies about where their jobs should run, but not require users to make low-level decisions about job placement (but would allow users to do so if they desired). These policies would allow a user to express their preferences about the tradeoff between performance, availability, and cost. In addition, a user might want to avoid their application running on a datacenter operated by a competitor, or stay within certain countries to obey relevant privacy regulations. To make this more precise, a user might specify that this is a Tensorflow job, it involves data that cannot leave Germany, and must be finished within the next two hours for under a certain cost.

大概需要下面这么几个功能: a) name service b) directory service c) accounting and charging across clouds.

Once an application has been designed to run across mul- tiple datacenters, the remaining cross-cloud issues can be addressed by the following three functionalities: (1) A uniform naming scheme for OSS services.

(2) A directory service which allows cloud providers to register their services, and applications to select a service based on their preferences. (3) An accounting and charging mechanism across clouds.

4. peering between clouds

在多个云之间相互传输,这里主要就是数据的迁移,这个迁移成本还需要考虑进去。目前还没有说多个cloud vendors之间合作通过high speek links传入来减少成本,如果有办法可以使得多个cloud vendors都受益的话,那么其实这件事情是有可能的。本质上还是经济问题。

We will call this form of pricing “data gravity” pricing, and it creates a strong incentive for users to process data in the same cloud in which it currently resides. Still, moving data from one cloud to another can still be the most cost-effective option, especially for jobs where the computation resources are much more expensive than the data transfer costs. For example, consider ImageNet training which involve a 150GB dataset. It costs about $13 to transfer it out of AWS, but, according to the DAWNBench2, it costs over $40 to train ResNet50 on ImageNet on AWS compared to about $20 to train the same model on Azure. Given these numbers, it would be cheaper to move the data from AWS and perform training on Azure, instead of performing the training in AWS where the data is. Thus, while data gravity pricing does inhibit moving jobs, in some cases moving jobs is still worthwhile.

To our knowledge, current pricing policies for exporting data are independent of the cloud the data might be going to. One alternative that we have not seen explored to date is for clouds to enter into reciprocal data peering arrangements, where they agree to allow free exporting of data to each other, and to connect with high-speed links (presumably at PoPs where they both have a presence). This would make data transfers both fast and free, lowering the data gravity between two peering clouds and enabling greater freedom in job movement. As we argue below, this may solve some of the underlying incentive problems inherent in creating the compatibility and intercloud layers.

5. Speculations About The Future

compatibility layer上,smaller cloud vendors会跟感兴趣,这样才能切入更大的市场。

In addition, while large incumbents might not be happy about a compatibility layer, we expect smaller cloud providers will embrace such a layer. For smaller cloud providers, offer- ing proprietary interfaces may not be preferable to adopting a more widely supported standard. By doing so, these smaller providers would have access to a larger market share (i.e., users who have adopted the compatibility layer as their set of APIs) and could compete on price, performance, or various forms of customer service.

一旦compatibility/intercloud layer建立好的话,什么公司会推进这个peering layers呢?作者把cloud vendors分成为两类:standalone & commodity cloud providers. 两者的区别就是standalone希望锁住用户,而commondity希望不断地整合多个cloud来降低成本。commondity cloud providers之间会形成sky联盟,创建这个peering layers.

We think that once a compatibility layer and an intercloud layer are in place, cloud providers will fall into two cate- gories. There will be stand-alone cloud providers who try to lock customers in with proprietary interfaces and data export fees. These providers will typically be large enough so that they have the resources to offer a variety of pro- prietary services. However, in contrast to today, we think there will also be commodity cloud providers who directly support the compatibility layer and agree to reciprocal data peering with other commodity cloud providers. These com- modity providers, taken together as a whole, form the Sky, which offers a unified interface to a set of heterogeneous and competing cloud providers.

Why do we believe the Sky will happen? It rests on the nature of innovation in the two classes of providers. In a competitive market, the stand-alone providers compete with each other, and with the Sky. The commodity providers also compete with each other within the Sky, and collectively compete with the stand-alone providers. In terms of tradeoffs, the stand-alone providers have higher margins (because their customers have exit barriers) but must innovate across the board to retain advantages for their proprietary interfaces.

In contrast, the commodity providers have lower mar- gins, but can innovate more narrowly. That is, a commodity provider might specialize in supporting one or more services; jobs in the Sky that could benefit from these specialized ser- vices would migrate there. For example, Oracle could provide a database-optimized cloud, while a company like EMC can provide a storage-optimized cloud. In addition, hardware manufacturers could directly participate in the cloud econ- omy. For example, Samsung might be able to provide the best price-performance cloud storage, while Nvidia can provide hardware-assisted ML services. More excitingly, a company like Cerebras Systems, which builds a wafer-scale accelerator for AI workloads, can offer a service based on its chips. To do so it just needs to host its machines in one or more colo- cation datacenters like Equinix and port popular ML frame- works like TensorFlow [24], PyTorch [37], MXNet [27] — thus providing a compatibility layer — onto Cerebras-powered servers. Cerebras only needs to provide processing service; all the other services required by customers (such as data storage) can run in existing cloud providers. In contrast, to- day, a company like Cerebras has only two choices: get one of the big cloud providers like AWS, Azure, or GCP to deploy its hardware, or build its own fully-featured cloud. Both are daunting propositions.