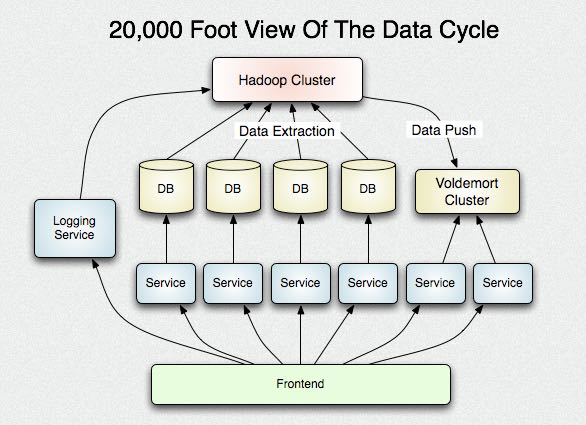

Building a terabyte-scale data cycle at LinkedIn with Hadoop and Project Voldemort

The fundamental fact of filesystem access is that you may or may not be accessing the underlying disk depending on whether your request can be served by the OS’s pagecache or not. A pagecache hit on an mmap’d file takes less than 250 nanoseconds but a page miss is around 5 milliseconds (a mere twenty thousand times slower). Any fancy data structure we build is likely to reside in-memory. Hence it would only help the lookups for things that would be in page cache anyway (since the process of loading them into memory would put them there) and so lookups on these would be fast no matter what. And worse this in-process lookup structure will likely steal memory from the pagecache to store its data, and since this will duplicate things in the pagecache it is extremely inefficient. Thus even if we manage to improve the lookup time for the things in our process memory, it is already quite low; and by doing so we use up memory that moves more requests out of the ns column and into the ms column.(不要自己在搞in-process查询结构)

To take advantage of this we have a very simple storage strategy that exploits the fact that our data doesn’t change–all we do is just mmap the entire data set into the process address space and access it there. This provides the lowest overhead caching possible, and makes use of the very efficient lookup structures in the operating system. Since our data is immutable, we don’t need to leave any space for growth and can tightly pack the data and index. Since the OS maintains the memory it can be very aggressive about this cache, and indeed it will attempt to fill all free RAM at all times with recently used pages. In comparison Java is a very inefficient user of memory since it must leave lots of extra space for garbage collection, etc. Plus anyone who has gotten intimate with Java GC tuning will not object to moving things out of the Java heap space.(将部分内存管理放置到JVM堆空间之外)

The actual method for transferring data is pluggable. The original prototype used rsync in hope of efficiently supporting the transferring of diffs. However, this has two practical problems. The first was that the rsync diff calculation appears to be quite expensive, and half of the expensive calculation is done on the live server. Clearly if we want to do diffs, that too should be done on the batch system (Hadoop) not the live system (Voldemort). In fact due to this heavy calculation rsync was actually slower than just copying the whole file, even when the diff was rather small (though presumably much more network efficient). The more fundamental problem was that using rsync required copying the data out of HDFS to some local unix filesystem–which had better have enough space!–to be able to run rsync. This copying took as long as the data transfer to Voldemort, and meant we were copying the data twice.(使用rsync在计算diff方面开销非常大)

Future work

- Incremental data updates

- Improved key hashing

- Compression

- Better indexing

The idea of a 204-way page-aligned tree instead of a binary tree was mentioned above. Each set of 204 20-byte index entries would take 4080 bytes which with 16 bytes of padding would then be exactly page aligned for a 4k page. This would mean the first 4k page of the index file would contain the hottest entries, the next 204 entries would contain the next hottest, and so forth. Thus even though the number of comparison necessary to locate an entry would not asymptotically improve the maximum number of page faults necessary to do an index lookup would decrease substantially in practical terms (to 4 or 5 for a large index).(改进index文件结构与page cache对齐)

This is not the optimal tree structure for an immutable tree such as ours, though. A much better approach to this problem was brought up by Elias who was familiar with the literature on cache-oblivious algorithms, and was aware of a cache-oblivious structure called a van Emde Boas tree